By Judith Dupré, Portfolio Guest Blogger

One World Trade Center boasts some staggering statistics—the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere, the fastest elevators in the Americas and the strongest concrete ever used, among many record-busters. It is the most advanced skyscraper ever built, after all.

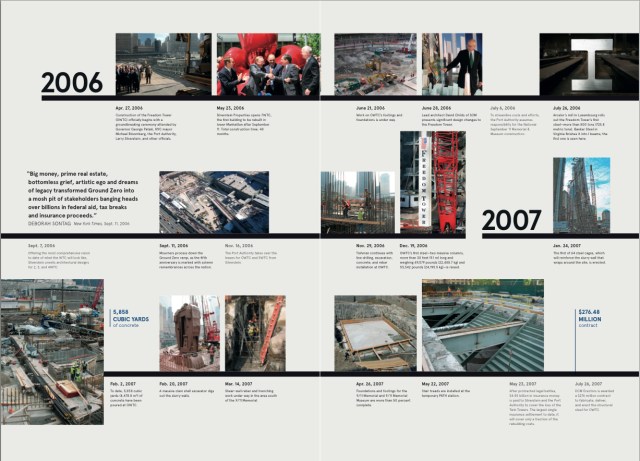

A timeline of historic construction photographs, shot by the Port Authority over the past decade, provides a glimpse into the heroic business of building a skyscraper.

But the most extraordinary statistic about the new World Trade Center is this: No lives were lost during the rebuilding. More than any other measure, this is the benchmark of the extreme care, precision and experience that the Port Authority has devoted to this most precious of sites.

My father, who has a knack for coining new phrases, speaks of events marked with the “asterisk of sorrow” to describe circumstances whose outcome has been influenced by grief. The WTC’S reconstruction was so asterisked—and inspired an unprecedented outpouring of ingenuity and hard work. A state-of-the-art enterprise, the project required the skills and brawn of thousands of Port Authority employees and contractors. Their numbers included architects, engineers, planners, financiers, as well as welders, electricians, riggers, painters and plumbers.

Everyone was the best at his or her job, that was a given. But each person also had to possess the wisdom and expertise to collaborate — so everyone else could give it their best. And they did. For the past fifteen years, the people of the Port Authority have stepped up, given it their all and gotten the job done, no matter what.

No great enterprise is without controversy. Many hurdles—political, financial and structural—had to be overcome. Despite One World Trade’s minimalist appearance, every single floor, and nearly every piece of steel on the building is different. Similarly, nearly every one of the 13,000 glass panels that comprise its façade is unique. The concrete core demanded that New York City unions work together in a new way, so the lessons learned from 9/11 could be implemented.

Moreover, One World Trade went up in tandem with eight other buildings—2 WTC, 3 WTC, 4 WTC, 7 WTC, the Oculus Transportation Hub, the Vehicle Security Center, St. Nicholas National Shrine, and the National 9/11 Memorial and Museum—all of it intensely scrutinized, controlled by dozens of owners and subject to the tightest security measures ever implemented. Hovering like a black cloud was the 2008 recession, which stalled construction everywhere. From this demanding framework, the World Trade Center emerged. Frankly, given all the challenges, it should not have, but it did because so many people cared so much.

As remarkable as the above ground structures are, much of what is marvelous about the WTC cannot be seen. An invisible world exists underground. There, each structure depends on its neighbors—one building’s roof is another’s floor. Interdependent, they form a Rubik’s Cube of shared foundations, utilities and mechanical systems. Linked to the Transportation Hub, they connect to a vast network of commuter lines and welcoming, underground pedestrian routes. Together, they represent one of the most profound collaborations in human history.

Many people shared personal, moving stories with me. Steve Plate, chief of major capital projects, cited the dedication of the 9/11 Memorial, when the Port Authority pulled out all stops so it could be completed for the tenth anniversary.

“The workers knew that September 11 was really for the families,” Steve said, “but on their own accord they got together and decided to have a moment.” On the Friday morning before the dedication, everyone stopped working and took off their hard hats for a moment of silence. “All the cranes . . . blew their horns at the same time, and they dropped the booms of the cranes, and faced them toward the pools in reverence,” Plate recalled.

One World Trade Center soars. With the other Trade Center buildings, it provides thousands with a place to reflect, work, eat and shop. The belief that all those things could be accomplished—backed up by the Port’s strenuous efforts, unparalleled expertise in large-scale construction and unswerving devotion to the people of New York, New Jersey and the nation—qualifies it as a masterpiece in my book.

Judith Dupré is the New York Times best-selling author of the new book, One World Trade Center: Biography of the Building