By Portfolio Editor Roz Hamlett

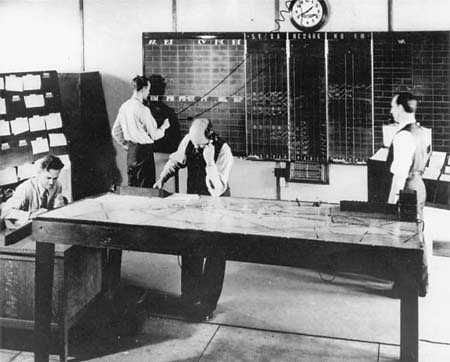

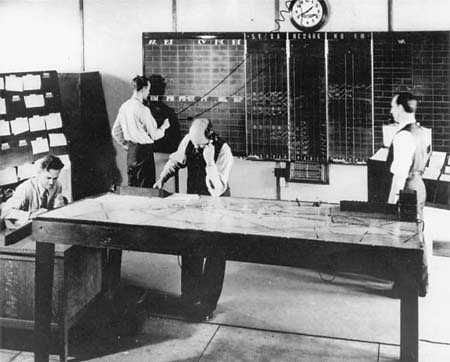

A flashback to Newark Airport’s history: operations at the first Airway Traffic Control Station in 1936 on a bleak and drizzly January afternoon. At the time, Newark Airport was becoming the busiest commercial airport in the nation. The airspace above Newark was growing more crowded. This was the same month and year that Howard Hughes would fly into Newark, after completing his record-breaking flight across the United States from Burbank, California.

By today’s standards, the air traffic control station was getting by on a wing and a prayer with tabletop maps, about four air traffic controllers and a blackboard of the sort used to teach school children.

The Newark control station had come into existence after a TWA flight crashed outside Kansas City, killing five persons, including the U.S. Senator for New Mexico. This accident sparked a Congressional probe and helped sow the seeds for the creation of an airline consortium in December, 1935.

Prior to the early 1930s, there wasn’t any need for a large organized system of air traffic control. Most flights took place on clear sunny days anyway. According to Newark Airport legend, William “Whitey” Conrad, who died in 2000 at the age of 95, “there was no controlling air traffic back then. It was a free for all – a half-assed operation, but it worked,” he said in a 1996 interview. Conrad is credited with developing the flag system at Newark for daytime traffic and the “biscuit gun” for use at night. The biscuit gun was a hand-held flashlight with reflectors.

The bill introduced to name the air traffic control tower at Newark Liberty International after “Whitey” Conrad.

Flights during periods of restricted visibility were not permitted. Still on the horizon were advances in aircraft control and navigation that would permit flight at night under conditions of restricted visibility. That is, with one notable exception – among the first attempts to illuminate an airfield at night took place at Newark Airport in 1929, with a bank of floodlights mounted on a platform and pointed at the runway. Unfortunately, the floodlights only threw light onto a small portion of the runway. By the late 1930s, the capability of aircraft to fly at night in marginal weather had improved.

The radio equipment of the 1930s was limited; there was no automated flight tracking system of any kind. Air traffic controllers did not have direct contact with the aircraft. Rather, communication between pilots and controllers was accomplished through a third party – an airline dispatcher or a radio operator.

If pilots had to fly in bad weather, they first had to file an instrument flight plan with the airline. The plan included the type of aircraft, departure and arrival information such as airports and times, and other information. The airline dispatcher forwarded this information to the Air Traffic Control unit, which then determined whether the route and altitude might conflict with other aircraft.

The controller wrote the flight plan on a chalkboard, and a note card was attached to a brass holder called a shrimp boat because it looked like a small fishing boat. These shrimp boats would be moved along the map, indicating the approximate positions of the aircraft as they flew toward their destinations. The positions were measured with calipers. This manual tool worked similarly to a compass – one end was set in a fixed location and the other used to measure distance. This is how controllers kept aircraft safely separated as they moved between airports.

The early air traffic controllers tracked flights with markers called “shrimp boats” and using calipers.

Earl Ward organized the Newark facility. He is pictured above (left) tracking a flight with the aid of a caliper.

As each plane progressed through airspace, the pilots transmitted their position to an airline company radio operator, who then relayed this information to the ATCU controller by telephone or telegraph. As information was updated on the blackboard, the shrimp boats inched across the map.

(Under such rudimentary circumstances, it’s a minor miracle that the inadvertent tossing of a pair of calipers into a trashcan, or a shrimp boat that slips beneath a table, were never cited as underlying causes of an aircraft collision.)

On June 7, 1937, the Department of Commerce (DOC) began to acquire the ATCUs from the airlines and staff them with federally-certified controllers. The federal government renamed these facilities airway traffic control stations. In May 1938, DOC became the licensing authority for all civilian air traffic controllers. This began federal air traffic control, and the stations became the forerunners of today’s Air Route Traffic Control Centers.

Air traffic control modernizes with navigation technologies such as radar.